Funding systems vary around the world, in our corner of the world both Australia and New Zealand have funding systems that are very function based. Both funding systems require a person to have been diagnosed with a disability to access the system, however what equipment is provided is based on what a person needs to be able to do, it is not related to the person’s underlying diagnosis or medical based needs. This means that in our funding reports we need to identify activities or tasks that a person wants or needs to be able to do, ideally something that can be measured through an outcome measure, and we link the features of the equipment to the relevant task.

However in the era of evidence based practice, finding evidence to support functional outcomes for equipment provision can be tricky, whereas more evidence is available to support medical benefits associated with equipment.

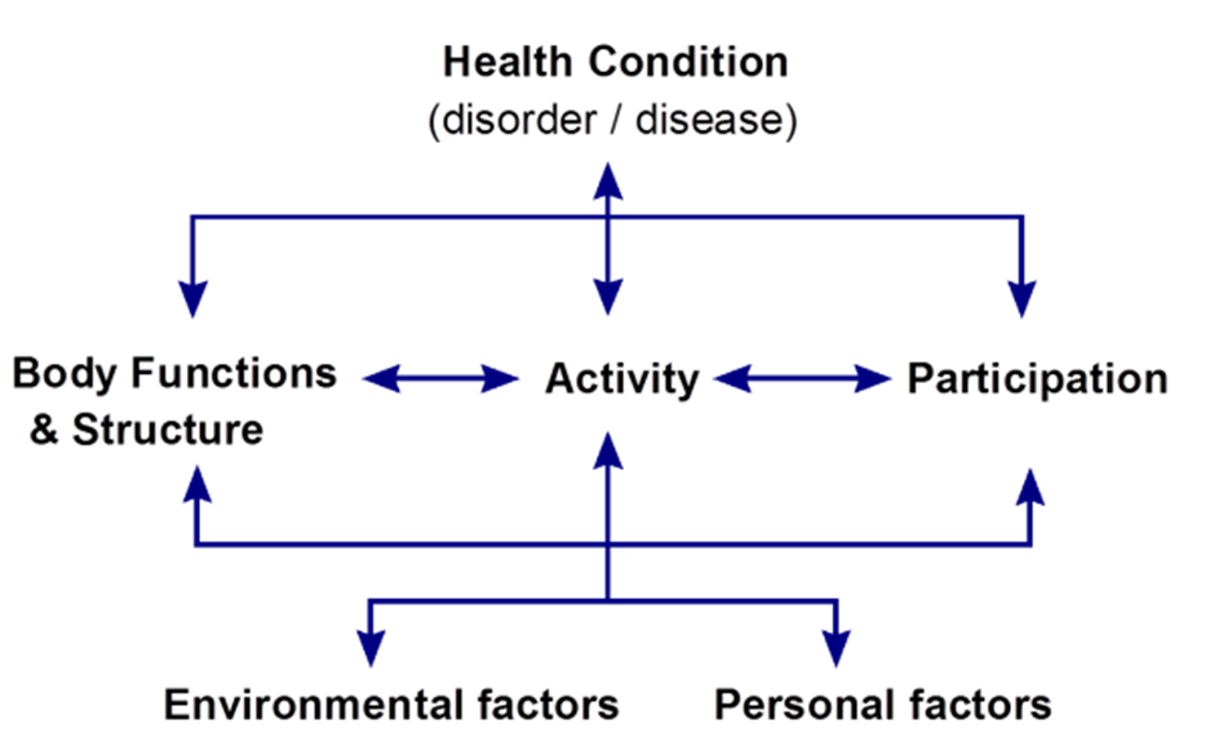

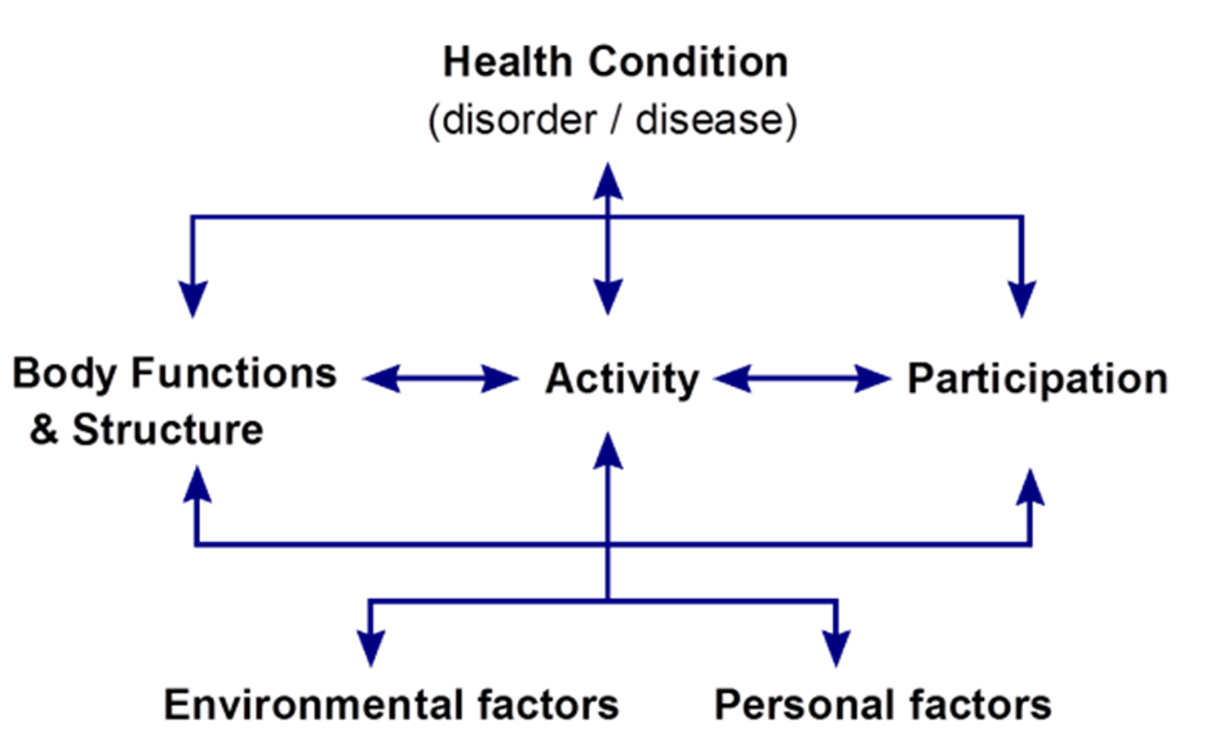

What is a medical benefit? Looking at the ICF, medical benefits are those that occur at a body structure and function level, as opposed to an activity or participation level. Internationally, there are funding systems that are based on medical necessity, with the equipment that a person receives being linked to their diagnosis and resulting body structure and function limitations.

The presence of ‘medical necessity’ based funding systems has influenced the research surrounding wheelchairs and seating, with a number of research articles being available to support the medical benefits surrounding wheelchairs. This information can be useful for therapeutic purposes but can be tricky to incorporate into a funding report that focuses on function.

Are the medical benefits offered by a piece of equipment separate to the functional benefits? Do we only mention the functional benefits in our funding reports?

Looking at the ICF can help answer these questions. We need to remember that each of the ICF domains does not exist in isolation – each domain is linked or influenced by the other domains. What we need to understand for a person is how these domains are linked, and how an intervention that may address an issue in one domain may influence factors in another domain.

The one domain that can be hardest to address in a function based funding system is the body structures and function domain, despite changes in this domain having the potential to influence to both the activity and participation domains. That said, some body structure and function limitations are easier to work through than others. Maintaining range of movement or managing spasticity are two body structure and function issues that are regularly raised, with the link to functional tasks being easily established. For example, regular standing helps a person maintain their range of movement in their lower limbs and this in turn helps maintain their ability to stand transfer in/out of their wheelchair, maintaining a standing transfer means they are able to continue to perform personal care tasks independently. Or the ability to use tilt, recline and elevating leg supports in their chair helps manage their spasticity and hence maintain a seated position in their wheelchair, maintaining a seated position in their wheelchair means they are able use their eye gaze communication device reliably to successfully communicate with family and friends.

Meanwhile other body structure and function limitations can be more challenging – for example bladder and bowel health. Standing has the potential to positively impact on bladder and bowel health, however the research on this is a little more varied as bladder and bowel health is a more challenging area to research. This doesn’t mean that you can’t incorporate this limitation into your funding reports, but it does mean that your clinical reasoning around this issue needs to be very robust. For example, you may be working with a person who has frequent urinary tract infections (UTI) and the team are keen to explore power standing as a means of reducing these. For this person multiple aspects need to be considered, such as

- How is the frequency of UTIs related to the impairment/disability?

- What medical options have been trialled and what is the outcome of these?

- What functional impact do the UTIs cause? Or how do the UTI’s impact on the person’s roles and responsibilities?

- What research is available to suggest that provision of this piece of equipment may be beneficial?

- Are there any potential contraindications for this person using this piece of equipment?

- What are the potential implications if the piece of equipment is not provided?

Is it possible to work through all potential medical benefits to their impact on function? Potentially not. One challenging medical benefit to work through is bone mineral density, which is another benefit that is associated with standing. Again we need to work through the above series of questions, however the answers to these questions may be challenging to incorporate into a funding report, with medical interventions potentially being more effective and low bone mineral density having a more obscure effect on a person’s roles and responsibilities.

Ultimately our funding reports require us to demonstrate good clinical reasoning and the process of justifying how an intervention at a body structure and function level impacts on the other ICF domains is another example of good clinical reasoning. If you’re not sure how sound your clinical reasoning is in your report, it is good practice to get a peer or colleague to proof read your report before you submit it, ideally the person reviewing your report does not know the person the report relates to. Having your reports peer reviewed can seem a little scary at first, however this review prior to submitting can save time in the process of getting a piece of equipment funded and help facilitate a good outcome for the person requiring the equipment.

Having trouble working through your clinical reasoning? The education team is here to help, drop us a line at education.au@permobil.com and we can help point you in the right direction.

Wanting a place to start with research? The RENSA position papers can help point you in the right direction. See here.

Rachel Maher

Clinical Education Specialist

Rachel Maher graduated from the University of Otago in 2003 with a Bachelor of Physiotherapy, and a Post Graduate Diploma in Physiotherapy (Neurorehabilitation) in 2010.

Rachel gained experience in inpatient rehabilitation and community Physiotherapy, before moving into a Child Development Service.Rachel moved into a Wheelchair and Seating Outreach Advisor role at Enable New Zealand in 2014, complementing her clinical knowledge with experience in NZ Ministry of Health funding processes.

Rachel joined Permobil in June 2020, and is passionate about education and working collaboratively to achieve the best result for our end users.